Running Tips for Longevity

Michael Clem PT, DPT

Running is one of the world’s most popular forms of exercise. Some running specialists, healthcare providers, and even paleoanthropologists would argue that we have evolved to be distance runners. Many believe that we did not evolve to be fast, as we are one of the slowest creatures on the planet, but to be very efficient at running for long periods of time and over great distances. Running is a great form of endurance exercise that can provide many health benefits including improved cardiovascular fitness, improved blood pressure, better management of blood sugar, lower cholesterol, enhanced immune system, improved mental health, increased bone health, decreased obesity, and reduced mortality just to name a few. Hundreds of millions of runners push off one foot and land on the other foot for thousands of steps every day. Humans are consistently shifting their body weight from one leg to the other over and over with running and just about every daily activity.

Running, as with most exercise routines, can be a difficult habit to maintain, even with the best intentions! As a westernized society we are less active, have an endless supply of calories at our fingertips, personal stress levels are high, sleep deprivation is becoming an epidemic, and sometimes we can’t prioritize physical activity into our busy schedules. Some people avoid running all together because they’ve had a previous running related injury. Others would argue inaccurately that it is bad for the joints. Lo et al 2 found that a history of running was not associated with a higher risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in a community population of over 2,000 people. Another study by Lo et al 3 found that running was “not associated with longitudinal worsening knee pain or radiographically defined structural progression.” In fact, the same study suggests that running may be beneficial for those with osteoarthritis as some participants showed a reduction in pain. A study by Ponzio et al 4, found that the arthritis rate in active marathoners was less than the rate of the general U.S. population

These studies build a strong case for running but we need to remember there are factors that can affect rates of injury. The two that are easiest to improve upon are running form and the total amount of running an individual does.

Running form continues to be debated and heavily researched. About 90% of runners land on their heels, 9% land in the middle of their foot, and about 1% land on their forefoot (typically elite distance runners and sprinters). There is evidence that landing on the heel can increase running related injuries, cause greater impact rates (the time it takes for the force to be applied), and the magnitude or peak amount of impact force. Shortening our stride so our feet are landing more underneath our bodies lessens the impact rates. Cadence or step rate is the number of steps that a runner takes in one minute. By increasing cadence, runners will automatically shorten their stride. Regardless of the foot strike pattern that one has, runners can reduce their impact and ultimately their risk for running related injuries.

Evidence by Heidersheit et al 1 has shown that simply by increasing self-selected cadence by 5-10% runners can reduce risk of injury and joint load. A cadence of 170-180 steps per minute is an ideal range to reduce the amount of impact and injury. One can use a watch or smartphone app that measures cadence to calculate an individual’s cadence. If a self-selected cadence falls below this range, it is recommended to increase cadence, so it is in the range or even greater! Using a metronome while running is a great way to learn a new “beat.” The goal is to land each foot on the beat of the selected cadence. Music streaming apps like Spotify have playlists that will even select music to a specific cadence for those who must listen to music while running.

Another way to improve form and reduce impact is by using a sound meter. Sound meters, which measure decibels, have been shown to teach runners to land “softer” and “quieter”. Sound meter apps can be found in both the Android and iPhone app stores. These apps provide a runner visual feedback as to how loud they’re hitting the ground. Placing the device on the front of the treadmill (not in the drink holder) with the sound meter on will allow them to watch a graphic and adjust their form so that the sound they are making on the treadmill is reduced. One article by Tate et al 5 suggests that using a sound meter app helped teach runners to land with less impact. If runners don’t use a sound meter, they can just try to be as soft and quiet as possible when running. Although sound does not correlate with impact forces directly, it has been shown that visual and verbal feedback to promote “softer” and “quieter” steps has resulted in runners landing with less impact.

Lastly, a lot of running related injuries occur when we run “too much, too soon.” Sprinkle in “too fast” and it becomes the perfect recipe for an injury. It is in a runner’s best interest to run with soft, quiet feet at a cadence of at least 170-180 steps per minute in which they feel their feet are landing underneath their body. Runners should maintain this form no matter how fast they go. Caution should be taken as one attempts to run faster, that is increase their miles or kilometers per hour. An increase in speed could potentially effect form which may increase a runner’s risk for injury. The goal is to sustain running for a longer period instead of trying to be fast. After all that is the definition of endurance exercise. All running should feel good. Keep in mind there is no perfect prescription for how much running we should do.

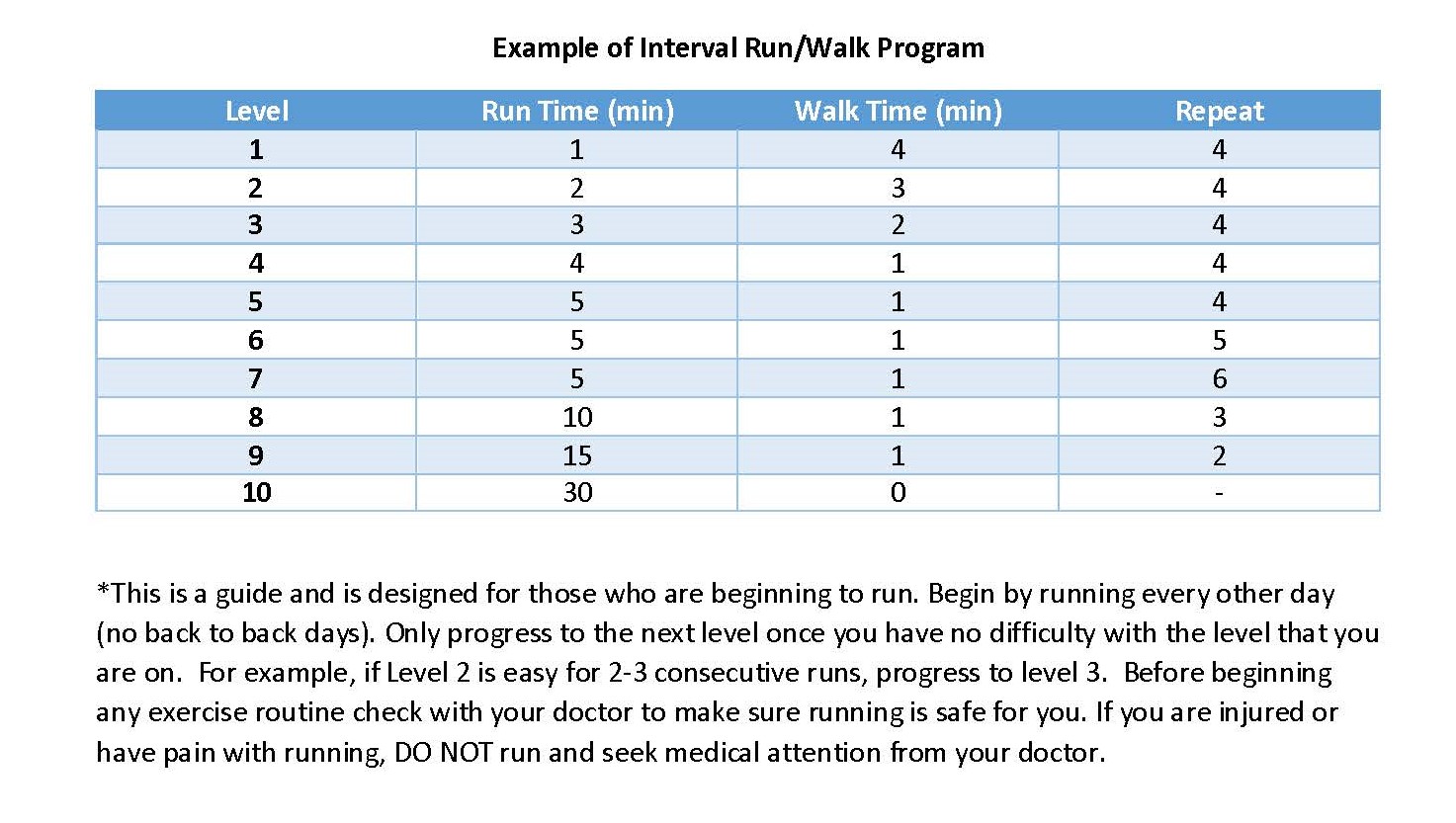

In order to get the most health benefits out of running and limit risk of injuries I have a few specific suggestions: Start slow (between 3.5-5.0 mph), use the recommended cadence (170-180 steps per minute), and think soft, quiet feet with all running. Use interval type training that is mixed with sets of walking and running periods. See this attachment as a guide. Using this interval approach helps increase the duration of running in a safe manner. Be flexible with the walking and running intervals as one may need to take longer walk breaks to recover between runs. Continue to increase the running time and decrease the walking until 30 minutes or more have been completed. Total running duration depends on each individual’s fitness goals. Just remember to always run well!

References

- Heidersheit, B., Chumanov, E., Michalski, M., Wille, C., Ryan, M. (2011). Effects of Step Rate Manipulation on Joint Mechanics During Running. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise., Feb 2011 43 (2), 296-302. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3022995/

- Lo, G., Driban, J., Kriska A., McAlindon, T., Souza, R., Petersen, N., Storti, K., Eaton, C., Hochberg, M., Jackson, R., Kwoh, K., Nevitt, M., Suarez-Almazor, M. (2017). History of Running is Not Associated with Higher Risk of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis: A Cross-sectional Study From the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 February ; 69(2): 183–191. doi:10.1002/acr.22939.

- Lo, G., Musa, S., Driban, J., Kriska A., McAlindon, T., Souza, R., Petersen, N., Storti, K., Eaton, C., Hochberg, M., Jackson, R., Kwoh, K., Nevitt, M., Suarez-Almazor, M. (2018). Running does not increase symptoms or structural progression in people with knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Clinical Rheumatology (2018) 37:2497–2504 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4121-3

- Ponzio, D., Syed, U., Purcell, K., Cooper, A., Maltenfort, M., Shaner, J., Chen, A. (2018). Low Prevalence of Hip and Knee Arthritis in Active Marathon Runners. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2018;100:131-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.16.01071

- Tate, J., Milner, C. (2017). Sound-Intensity Feedback During Running Reduces Loading Rates and Impact Peak. The Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Physical Therapy. 47 (8), 565-569. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.7275